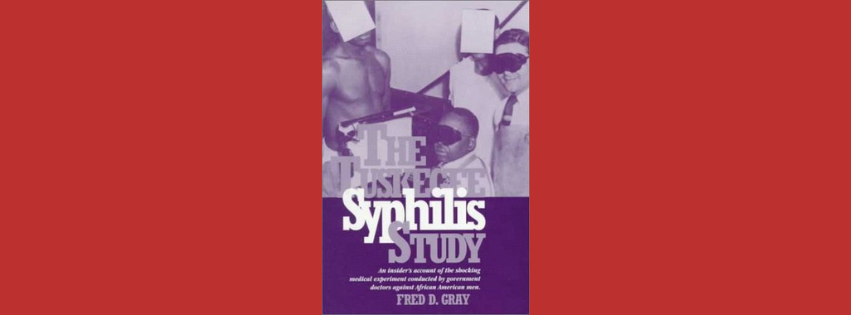

Introduction: A Study in Horror—Disguised as Healing

In the shadow of Jim Crow laws and racial apartheid in America, a small town in Alabama became the site of a four-decade-long medical betrayal. In a time when Black communities were desperate for healthcare, doctors in white coats offered hope—but administered lies.

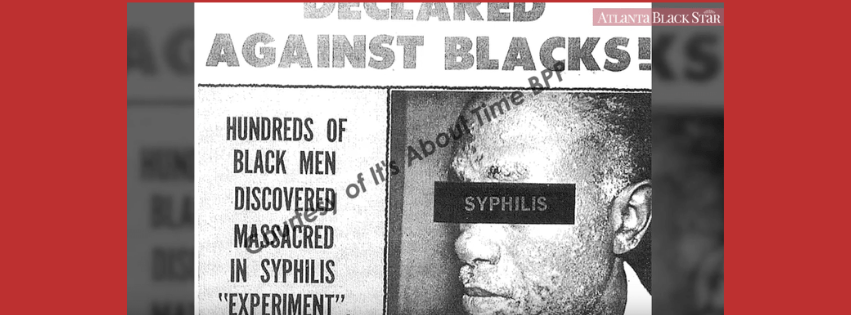

The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment was not simply unethical. It was a calculated, racially targeted deception, sanctioned by the United States government, and shielded by the medical establishment for 40 uninterrupted years.

But to understand its horror, we must go deeper than the headlines. We must unearth the obscure documents, quiet complicity, psychological manipulation, and systemic coverups that made this one of the most disturbing chapters in modern medical history.

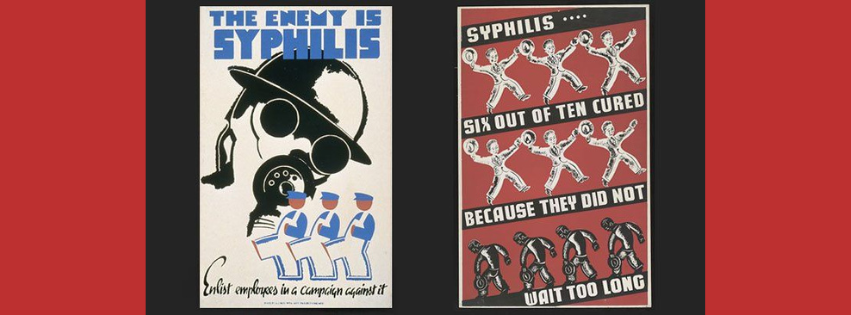

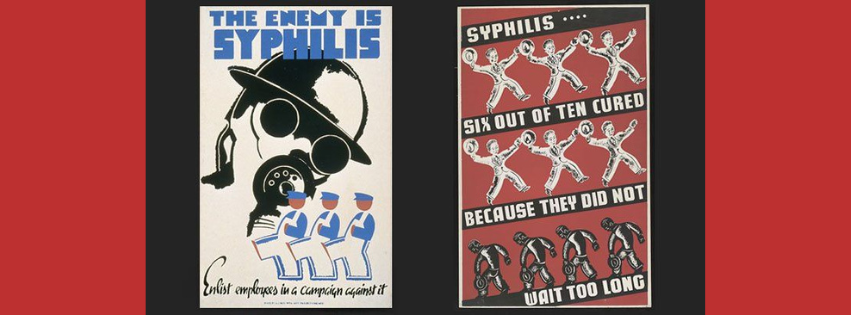

📜 The Setup: A Deceptive “Study” Masked as Medical Outreach

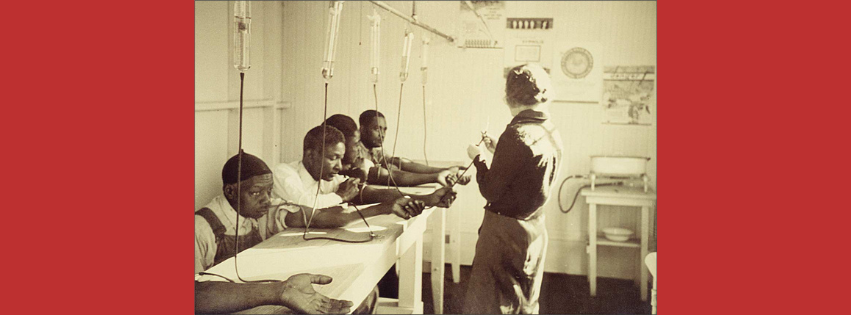

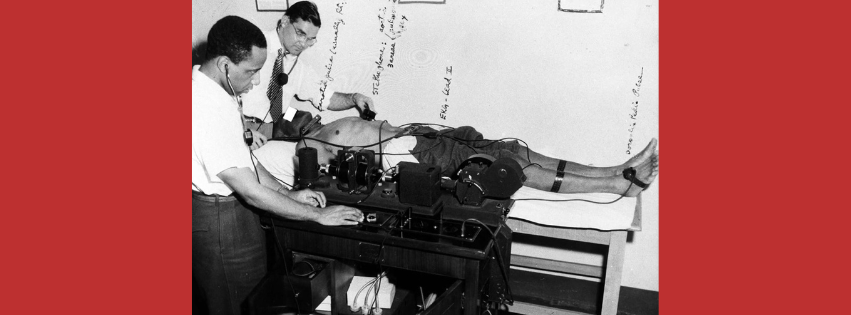

In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS), in collaboration with the Tuskegee Institute, launched a study to observe “the natural progression of untreated syphilis in the Negro male.” The target? 600 Black men from Macon County, Alabama—a deeply segregated and impoverished region.

- 399 men had latent syphilis

- 201 men were uninfected controls

These men were not told the truth. They believed they were being treated for “bad blood,” a vague Southern term encompassing everything from fatigue to anemia to syphilis.

What they received instead was 40 years of manipulation.

😷 The Lie That Kept Growing: Little-Known Manipulations

While the general facts are widely reported, here’s what most people don’t know:

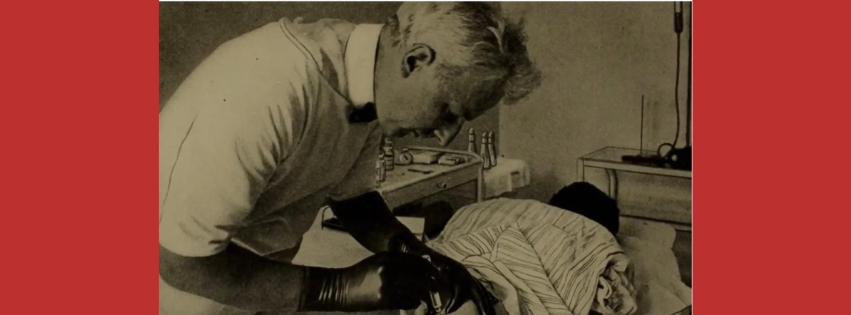

1. Spinal Taps Were Marketed as “Special Free Treatment”

The Public Health Service gave men spinal taps to study neurological syphilis, but advertised it as “last chance for special treatment.” This letter was mailed to participants, creating false urgency and further betraying their trust.

2. The Doctors Created a Local Network of Misinformation

Local Black doctors and nurses were co-opted to maintain the illusion, often without full knowledge of the study’s purpose. Their involvement lent credibility, making the lies harder for the men to question.

3. Death Certificates Were Intentionally Manipulated

Even in death, deception persisted. Syphilis was often omitted from death certificates to hide its role in the participant’s demise.

4. The Men Were Deliberately Prevented from Accessing Care

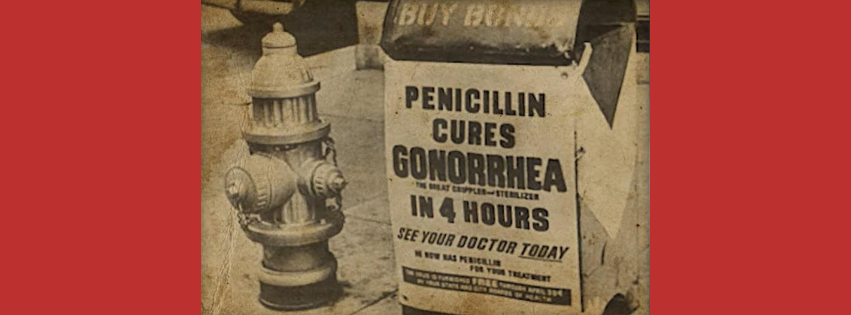

When the National Venereal Disease Treatment Program launched in the 1940s, Tuskegee participants were intentionally kept off the lists that would have qualified them for free penicillin.

This wasn’t medical negligence. This was strategic denial.

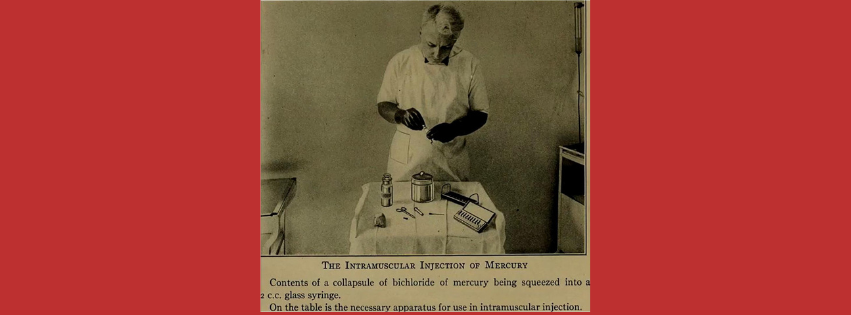

💊 The Penicillin Betrayal: A Hidden War Against the Cure

Penicillin became the recommended treatment for syphilis in 1947, but Tuskegee participants were blocked from receiving it—even when they sought help outside the program.

- Doctors sent memos instructing clinics not to treat them.

- Fake medical documents were used to deny them prescriptions.

- The men were labeled as part of a “special study group” to keep other physicians away.

Some men, desperate and suspicious, moved cities to get treatment—only to be tracked down and discouraged from seeking help by USPHS agents.

This is one of the few experiments in history where the cure was considered a contaminant to the study.

🩸 Generational Devastation: The Victims Beyond the Charts

This experiment didn’t just destroy 600 lives. It infected generations:

- At least 28 wives contracted syphilis

- 19 children were born with congenital syphilis

- Many families were left destitute after losing the primary breadwinners

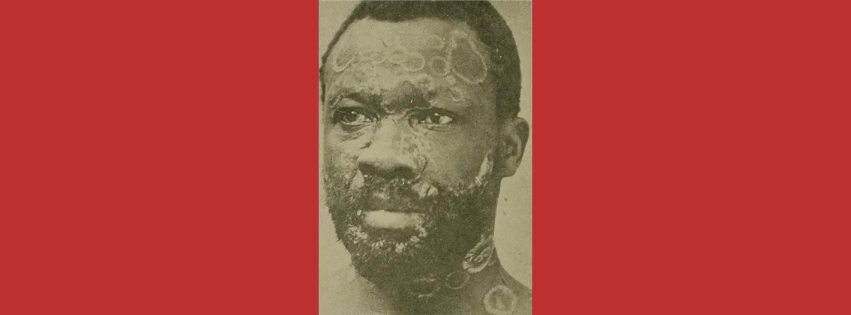

- Survivors endured chronic pain, blindness, paralysis, and psychiatric breakdowns

Yet, until the 1970s, many families still believed the government had tried to help.

🔍 The Cover-Up Culture: Medicine, Media & Silence

For decades, prestigious medical journals published the study’s results without criticism.

- Articles appeared in JAMA, the American Journal of Public Health, and Archives of Internal Medicine.

- No peer reviewers ever raised ethical concerns.

- Harvard, Yale, and Johns Hopkins all used the data for lectures and research—without condemning it.

This silence from academia and media allowed the horror to fester in secrecy.

The system didn’t fail. It was designed to operate this way.

🧨 The Whistleblower Who Broke the Spell

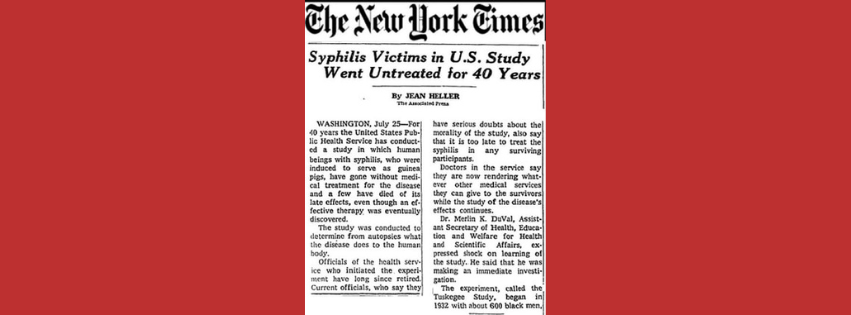

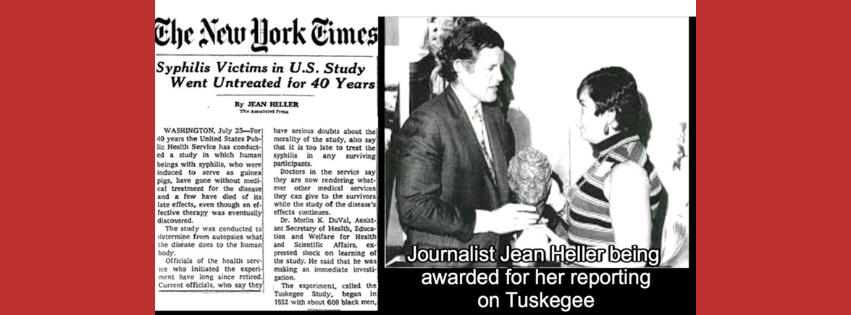

The lid blew open in 1972, not because of a moral awakening—but due to a young investigator named Peter Buxtun, who repeatedly complained to his superiors.

After being ignored, he leaked the study to Jean Heller, an investigative journalist with the Associated Press. Her front-page story shocked the world.

This led to:

- A Senate investigation

- Public hearings

- A class-action lawsuit

- The creation of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and informed consent laws

But notably:

No doctor was criminally charged.

No medical license was revoked.

🗣️ “I’m Sorry”: The President’s Apology—25 Years Too Late

On May 16, 1997, President Bill Clinton issued an official public apology.

“The United States government did something that was wrong—deeply, profoundly, morally wrong. To our African American citizens, I am sorry.”

Five survivors were present in the White House. They wept—not just from the apology—but from the validation they had long been denied.

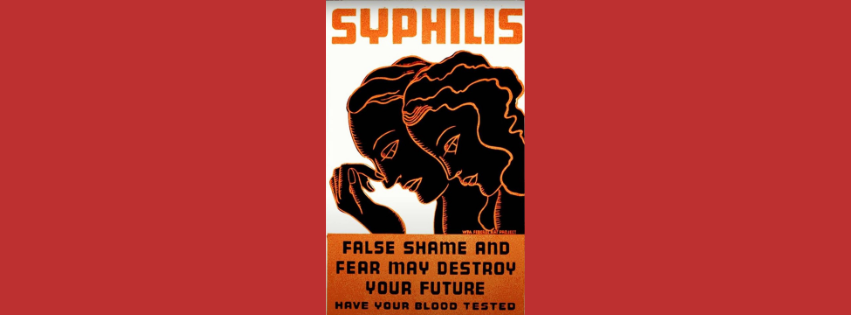

🧠 Psychological Toll: Not Just Physical Wounds

Modern studies show that the Tuskegee experiment caused:

- Lifelong distrust in medical institutions

- Lower life expectancy among Black men

- Fear of clinical research participation

- Increased mortality from other treatable diseases due to fear of doctors

This has become known as “The Tuskegee Effect”, still observable today—especially during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, where vaccine hesitancy was disproportionately high in Black communities.

📚 Academic Revisions: A Legacy Still Being Unwritten

Despite reforms, many survivors’ families still:

- Lack access to full medical records

- Have limited or no compensation

- Experience ongoing psychological trauma

Activists and scholars now push for:

- More inclusive medical ethics training

- Curriculum changes in medical schools

- Community-based oversight of research

🎭 Did You Know? Lesser-Known Tuskegee Facts

| Fact | Description |

| Code Name: | Internally, the project was nicknamed “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Male Negro”—never intended to sound like treatment. |

| Classroom Studies: | Data from the study was shown in medical schools until the 1980s as legitimate research. |

| Nurse Rivers: | A Black nurse, Eunice Rivers, was one of the key liaisons. She believed she was helping the men, unaware of the full deception. |

| Presidential Awareness: | There’s evidence some officials in the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations knew about the study but remained silent. |

| Confidential Burial Arrangements: | The men’s autopsies were secured by secretly offering full funeral coverage to their families. |

🧭 What We Must Learn

The Tuskegee Experiment wasn’t just a failure of oversight—it was an intentional design built on racism, classism, and scientific arrogance. It reminds us that ethics must never play second fiddle to data, and that science without humanity is monstrous.

Never forget: The most dangerous words in science are “for the greater good.”

50 Unique Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

1. What made the Tuskegee Syphilis Study unique among unethical experiments?

It was the longest non-therapeutic experiment in history involving human subjects—spanning four decades.

2. Were the men in the study ever told they had syphilis?

No, they were told they had “bad blood,” a vague local term used to describe various illnesses.

3. Why was syphilis chosen for the study?

Because it was common in the South and had long-term, observable effects without immediate death.

4. How were participants recruited?

Through flyers promising free medical exams, meals, and burial insurance.

5. Was this experiment legal at the time?

Technically, yes—but there were no laws requiring informed consent in 1932.

6. How many total men were involved in the study?

600—399 with syphilis and 201 without.

7. Did any of the men try to leave the study?

Some did, but they were discouraged or misled by researchers.

8. What is “bad blood” in this context?

It was a local term for conditions like anemia, fatigue, and syphilis.

9. Was the local community aware of what was going on?

No, most believed the government was offering genuine medical aid.

10. Were any other racial groups studied?

No, the focus was exclusively on African American men.

11. Was penicillin ever offered to the participants?

No, despite it becoming standard care by the 1940s.

12. How did the government monitor the participants?

Through regular visits, check-ups, and deceptive letters.

13. Were there any female subjects?

Not directly, but many wives contracted syphilis from infected husbands.

14. Did children inherit syphilis from infected fathers?

Yes, congenital syphilis was a tragic consequence.

15. What was the long-term physical impact on survivors?

They suffered blindness, organ failure, and mental illness.

16. Who funded the experiment?

The U.S. Public Health Service, with support from Tuskegee Institute.

17. Were there any Black doctors involved?

Yes, a few were used to gain community trust, although most didn’t know the full extent.

18. Did the experiment violate the Hippocratic Oath?

Absolutely—it betrayed every medical principle of “do no harm.”

19. Were autopsies performed on the deceased?

Yes, in exchange for burial expenses.

20. Did any of the doctors express regret?

Some did later, but most remained silent during the study.

21. How did media play a role in uncovering the truth?

AP reporter Jean Heller’s expose brought the experiment to national attention.

22. What role did the CDC play?

It supported continuing the study even into the 1960s.

23. Why wasn’t the study stopped earlier?

Because it was considered “valuable research” on untreated syphilis.

24. Was anyone criminally charged?

No one was ever held legally accountable.

25. Did any academic institutions condemn the study?

Yes, after it was exposed—many distanced themselves from the project.

26. What is the “Tuskegee effect”?

It refers to the mistrust of healthcare systems among Black Americans due to the study.

27. What diseases are now compared to Tuskegee in ethical debates?

HIV/AIDS research and some COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy discussions.

28. Were participants isolated?

Not physically, but they were psychologically manipulated.

29. Were church leaders involved in promoting the study?

Some were used to encourage participation.

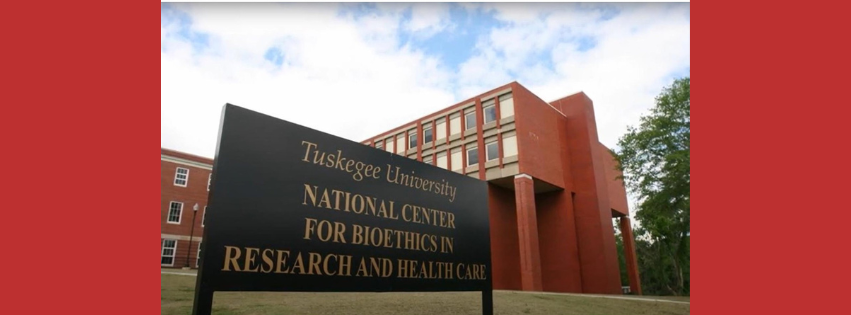

30. How is the study remembered in Tuskegee today?

With a museum and educational programs at the Tuskegee University.

31. Did medical journals publish data from the study?

Yes, including journals like JAMA.

32. What role did race play in the study’s rationale?

Researchers believed Black men were more sexually promiscuous and less intelligent—justifying unethical treatment.

33. Was there a medical oversight body?

No formal ethical review boards existed until after the study ended.

34. Did the experiment inspire any films or books?

Yes, including the documentary “The Deadly Deception.”

35. How did Bill Clinton apologize?

In a public ceremony in 1997, calling it “shameful.”

36. Are the families of victims still compensated?

Some receive limited benefits even today.

37. What was the role of the Tuskegee Institute?

It provided location and staff, but full involvement is debated.

38. How does the experiment affect Black Americans’ trust in medicine today?

It remains a major source of mistrust and reluctance to seek care.

39. Were death certificates manipulated?

Yes, syphilis was sometimes omitted as a cause of death.

40. Is there a memorial for the victims?

Yes, in Tuskegee, Alabama.

41. What laws changed as a result?

The National Research Act (1974), mandating IRBs.

42. Did survivors testify in court?

Some gave testimonies during legal and public hearings.

43. How did whistleblower Peter Buxtun discover the truth?

He worked in PHS and raised ethical concerns internally before going public.

44. Was the experiment seen as successful by its conductors?

Yes—shockingly, many saw it as a “scientific milestone.”

45. What role did class play in the study?

Poor Black men were targeted due to their economic vulnerability.

46. Were there similar experiments elsewhere?

Yes, the Guatemala Syphilis Experiment (1946–1948) is one example.

47. How has the study impacted medical education?

It is now a core case in bioethics and human rights classes.

48. What does the term “non-therapeutic” mean?

The study observed without providing treatment—unethical for a known disease.

49. Are there academic databases of all records?

Yes, but access is restricted for privacy and legal reasons.

50. What can we learn from this tragedy?

That science without ethics can become one of the most dangerous forces in society.

🧭 Conclusion: Remembering, Reckoning, Reforming

The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment is more than a historical footnote—it’s a scar on the conscience of science and society. Its legacy challenges us to uphold ethical integrity in research, especially when power, race, and science intersect.

Let us never forget the names, lives, and families behind the statistics. And let us ensure that history never repeats itself.