Content note: This article is detailed but non‑graphic. It focuses on verifiable facts, investigation methods, legal context, and long‑term impact.

TL;DR

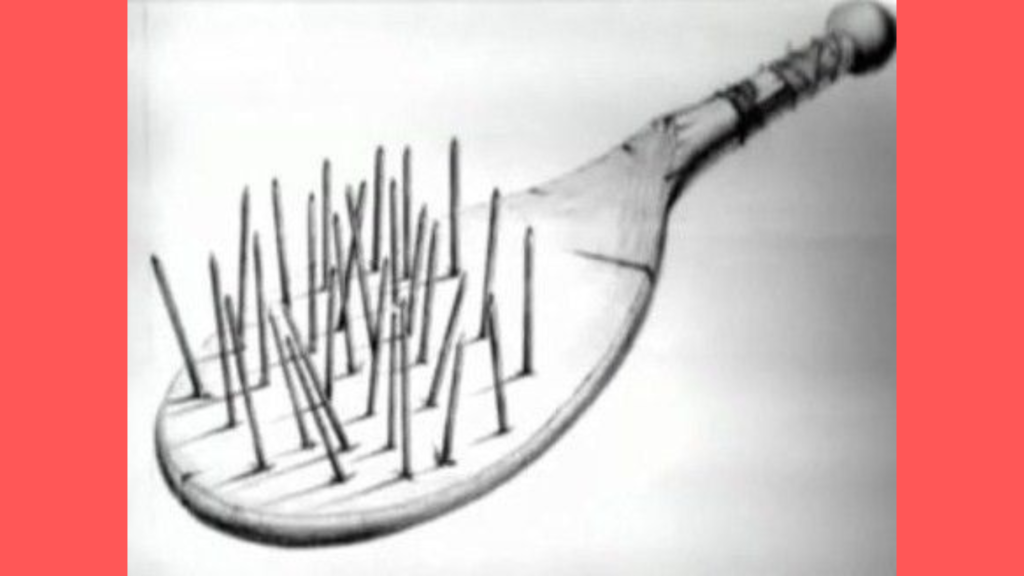

Albert Fish (1870–1936) is among the most disturbing American criminals of the early 20th century. Active primarily in the late 1920s–early 1930s, he abducted Grace Budd in 1928 and was ultimately traced and arrested after sending a letter that investigators linked to a chauffeurs’ association via a distinctive hexagonal seal on the envelope. Tried in White Plains, New York in 1935, Fish’s defense centered on insanity while the prosecution argued he was legally responsible. He was executed at Sing Sing in 1936. X‑rays famously revealed dozens of needles he had inserted into his pelvic region; contrary to persistent rumor, they did not short‑circuit the electric chair.

Table of Contents

- Why Albert Fish still matters

- Early life and pattern‑building

- America in the 1920s–30s: context that shaped the case

- Modus operandi: approach, pretexts, and movement

- The Budd family encounter: from newspaper ad to abduction

- Other attributed cases (overview)

- The letter that caught him: how a small hexagon unraveled the case

- Arrest: the rooming‑house lead and a razor at the door

- Inside the White Plains trial (1935): Wertham vs. the State

- Execution at Sing Sing (1936): myths vs. facts

- Psychological profile (non‑diagnostic): what experts debated

- Myth‑busting cheat sheet

- Why this case changed investigations

- Ethics of writing about true crime

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Suggested images + alt text

- SEO notes (ready to paste)

- Schema markup (FAQ + Article)

Why Albert Fish still matters

- Method over gore: The case is a masterclass in how tiny physical details (stationery, envelopes, typography) can crack a major investigation.

- Law & psychiatry: It spotlights the gap between clinical abnormality and legal insanity under the M’Naghten rule.

- Media literacy: Popular retellings are riddled with myths (e.g., needles disrupting the electric chair). Understanding what’s actually documented helps readers separate fact from folklore.

Early life and pattern‑building

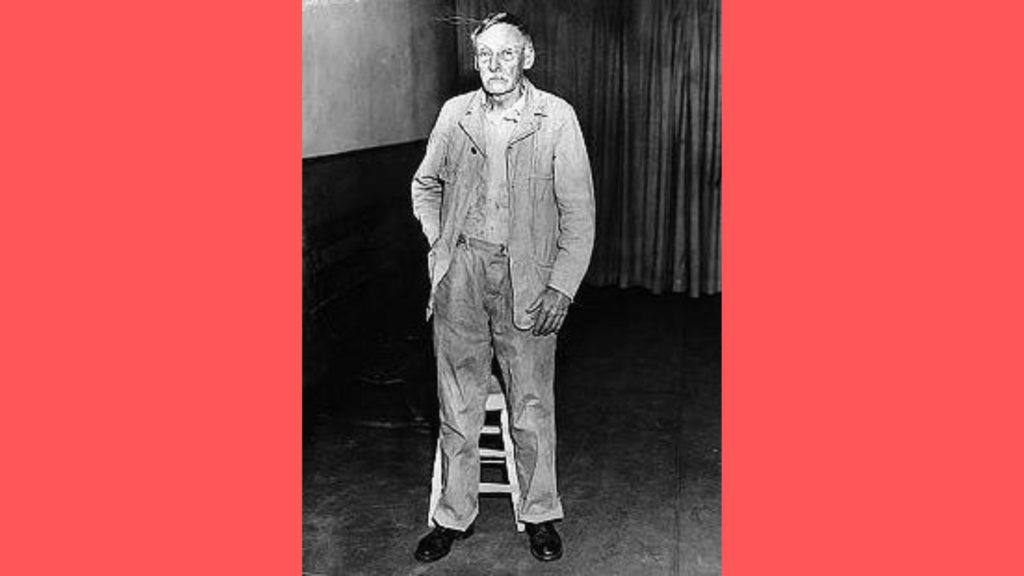

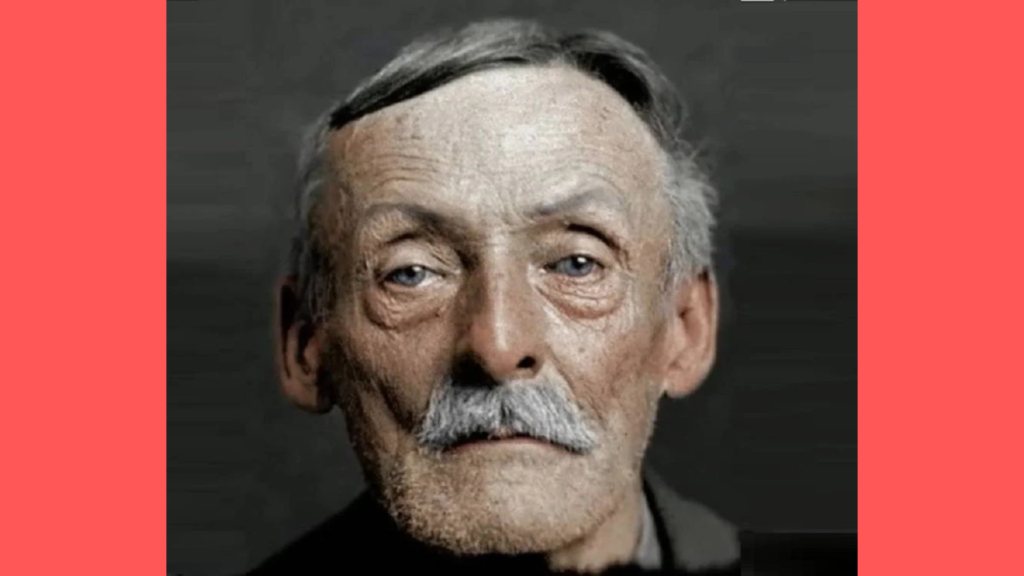

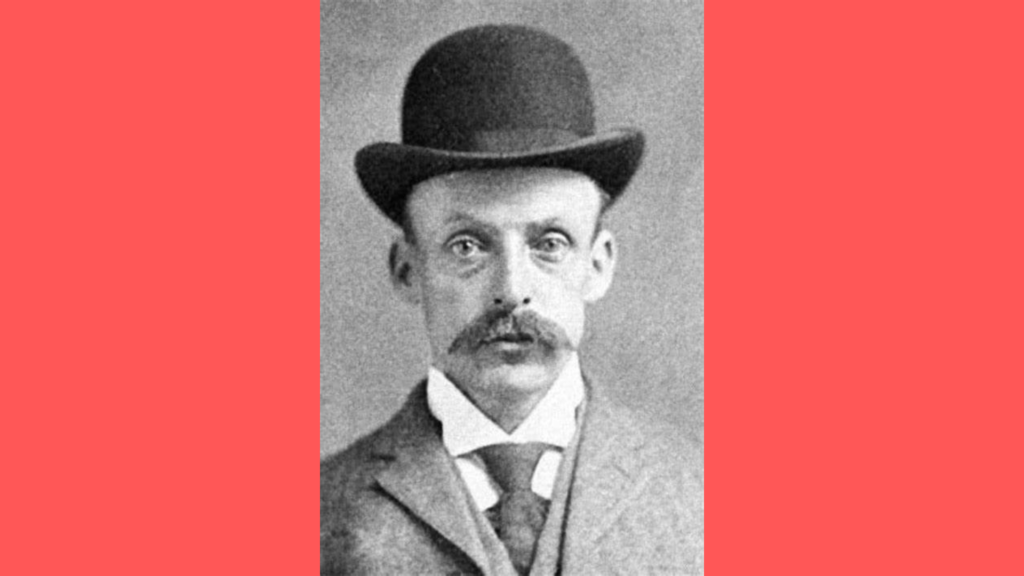

Born Hamilton Howard Fish in 1870 (Washington, D.C.), his childhood included the loss of his father and prolonged institutionalization. Accounts describe severe corporal punishment at the orphanage; Fish later reported linking pain with arousal, a pairing that dominated his adult life. By the 1910s–20s he had a record (including theft‑related arrest) and a pattern of sending obscene letters—behaviors that foreshadowed both compulsivity and boundary‑testing.

America in the 1920s–30s: context that shaped the case

- Urban growth & anonymity: New York’s rapid expansion created opportunities for predators to move unnoticed and use rooming houses to reset identity.

- Newspaper classifieds: Before digital platforms, help‑wanted and work‑seeking ads were a lifeline—easy entry points for fraudsters using kindly elder personas.

- Patchwork policing: Inter‑agency cooperation was improving but inconsistent; a clever local detail (like a stationery logo) could be more valuable than distant tips.

Modus operandi: approach, pretexts, and movement

- Persona: A frail, grandfatherly figure—nicknamed the Gray Man—who used sympathy as cover.

- Pretexts: Offers of farm work, errands, or small payments; invitations to supposed family events; gifts of sweets; or errands requiring a brief trip.

- Targeting: Children he perceived as unguarded or persuadable.

- Mobility: Trolley lines and trains widened his hunting ground; rooming houses enabled swift change of address and identity.

The Budd family encounter: from newspaper ad to abduction

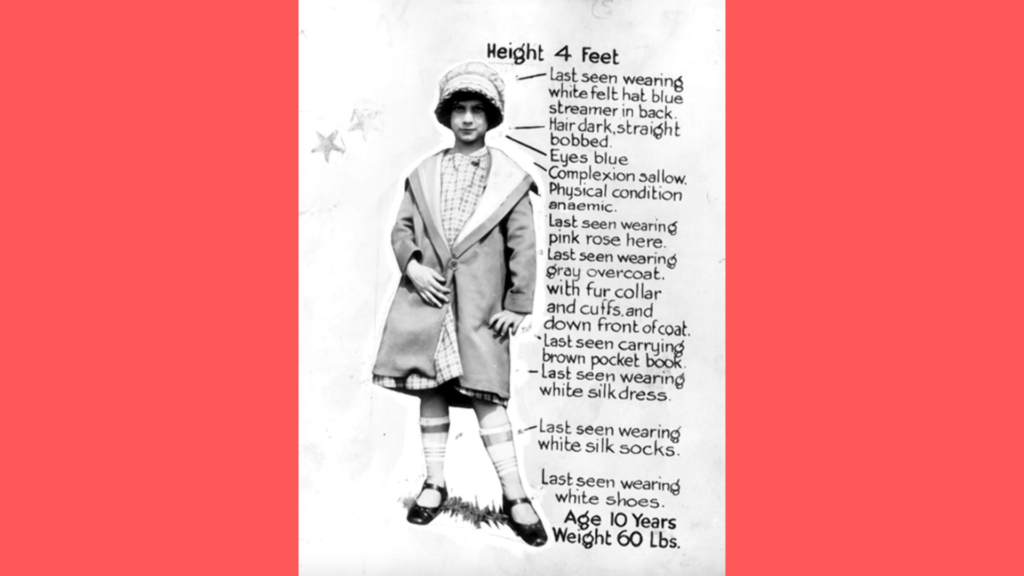

- The ad: A short note in a New York paper from a teen seeking rural work drew Fish’s attention.

- The alias: Fish arrived at the Budd home posing as “Frank Howard,” a modest, well‑off farmer.

- The pivot: After befriending the family and offering employment to their son, he convinced them to let Grace Budd accompany him to what he described as a birthday gathering. She did not return.

- Pre‑selection of site: Fish had previously scouted an isolated cottage (widely referred to as Wisteria Cottage) in Westchester County, suggesting deliberate planning rather than opportunism.

Other attributed cases (overview)

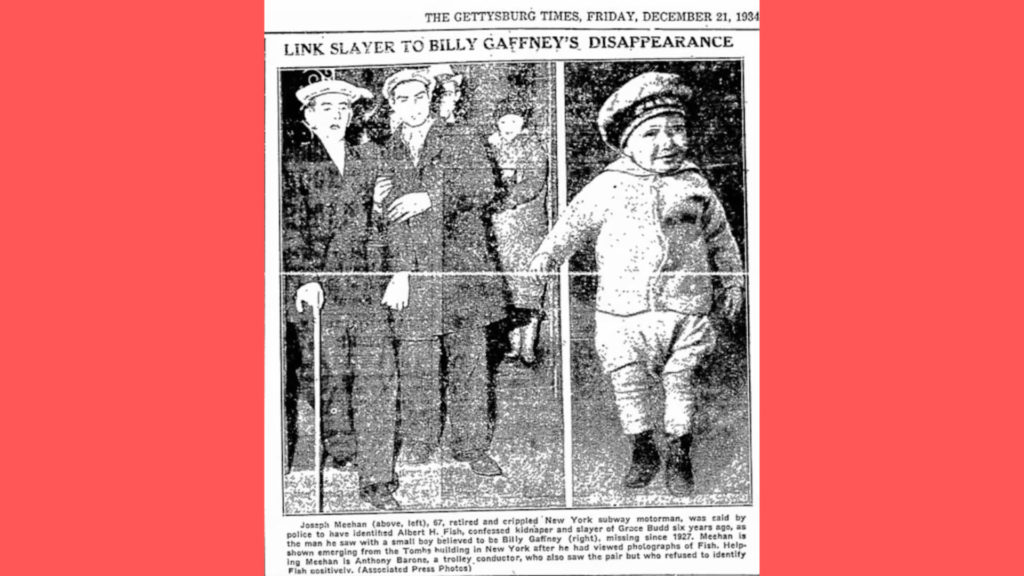

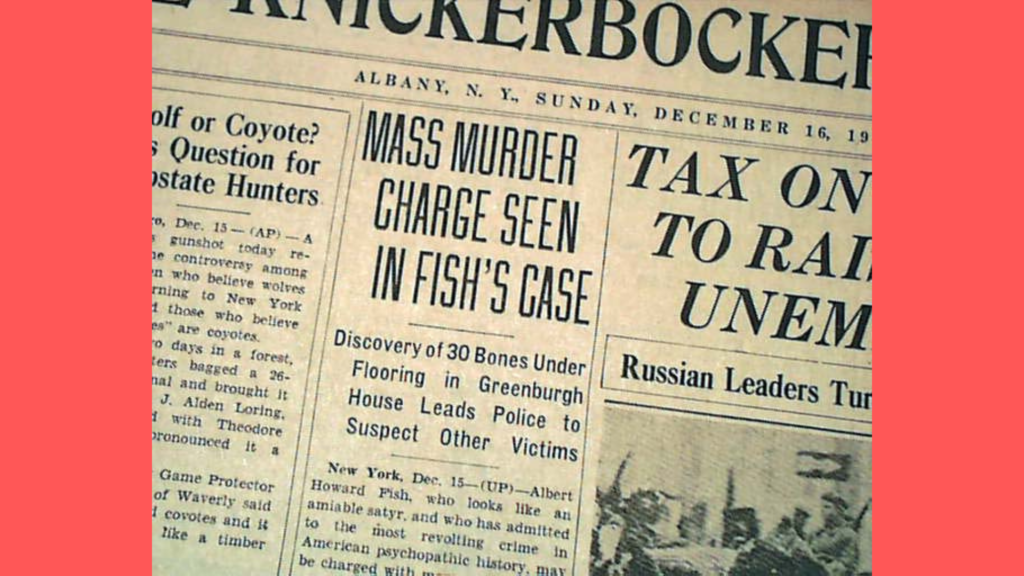

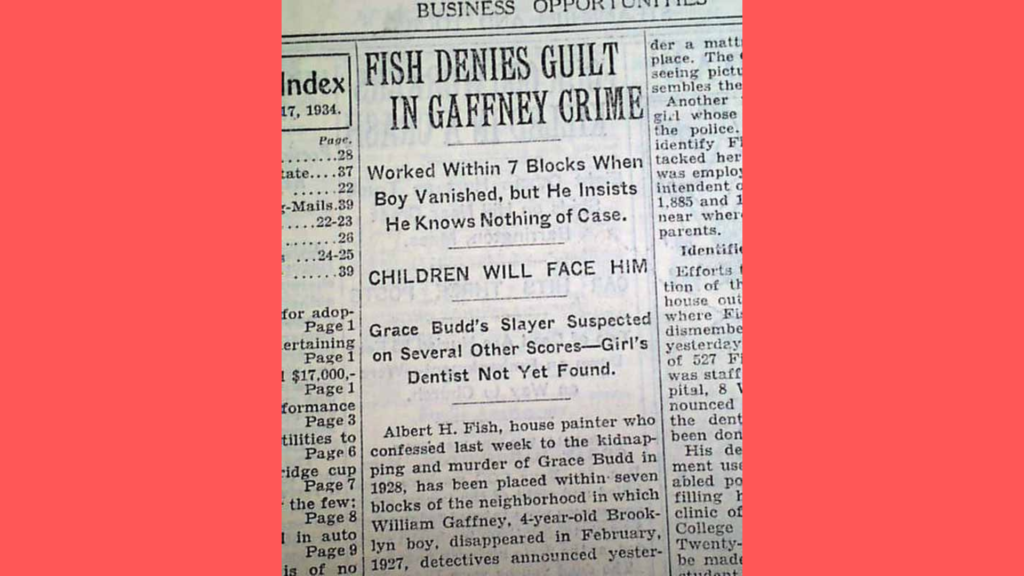

Several child disappearances and murders from the late 1920s were later linked to Fish by witness accounts and his own statements. Two names often cited in contemporary reporting and later analysis are Billy Gaffney and Francis McDonnell. While exact totals remain unverified, the pattern—luring, isolation, and ritualized behaviors—fits.

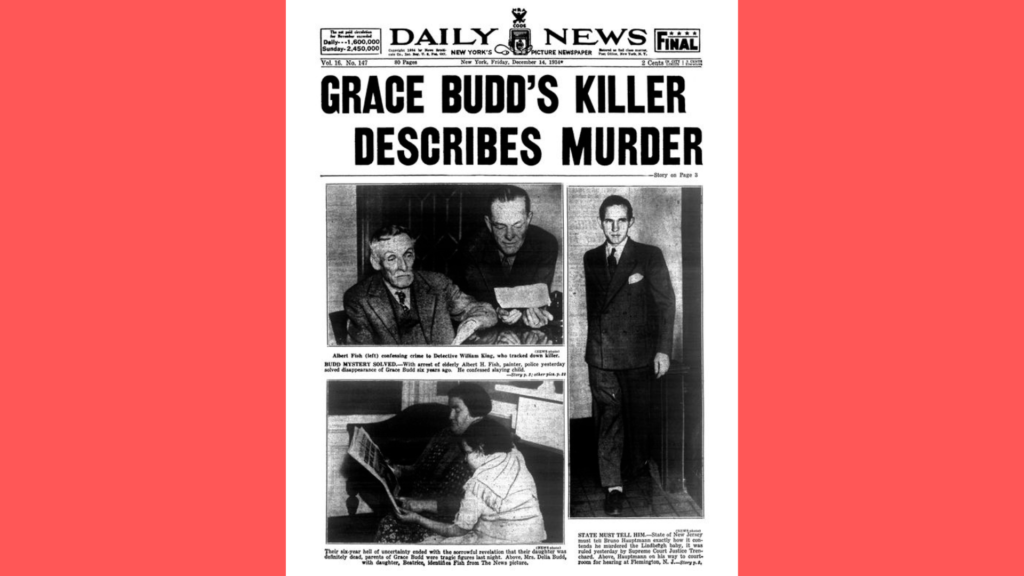

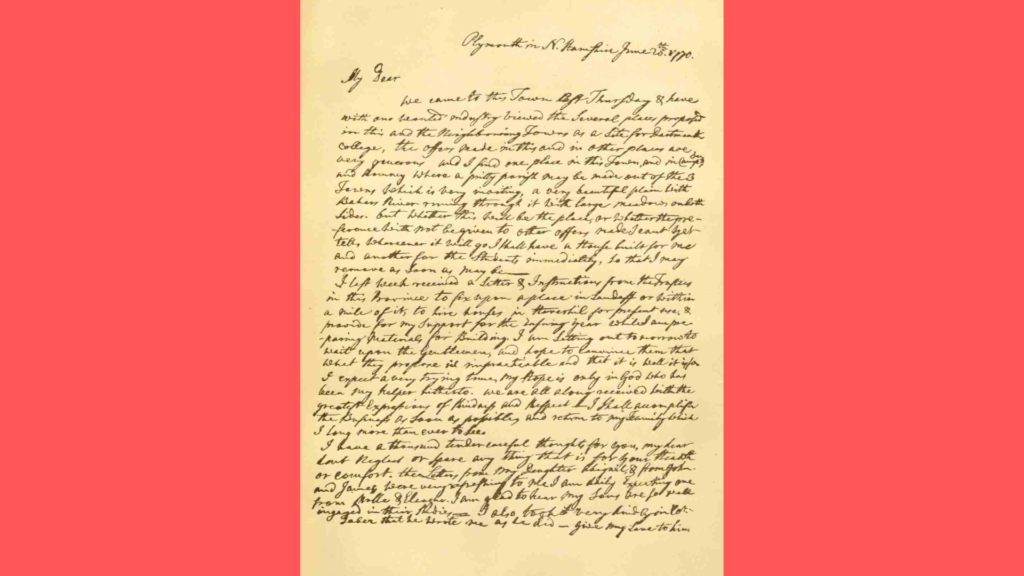

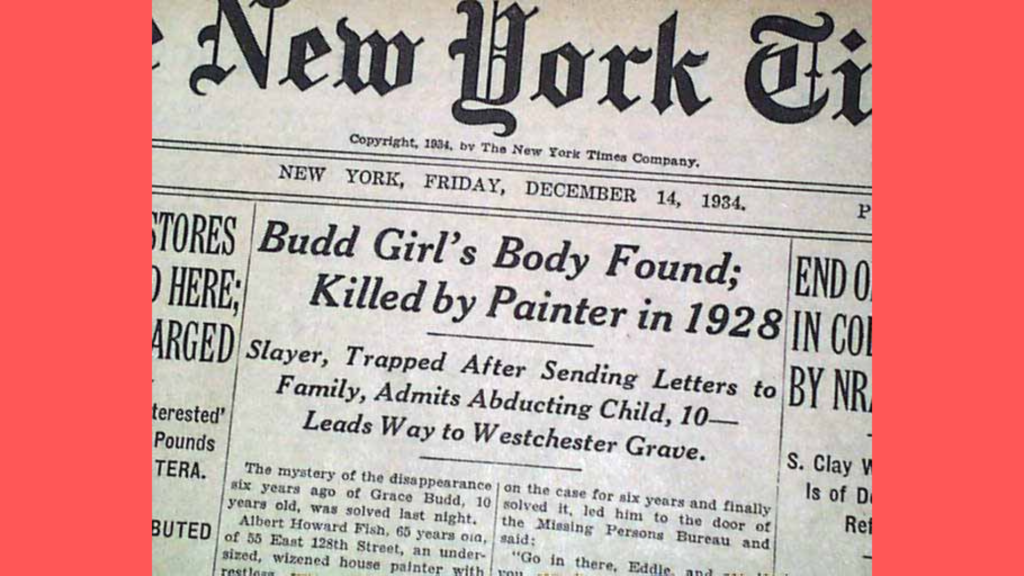

The letter that caught him: how a small hexagon unraveled the case

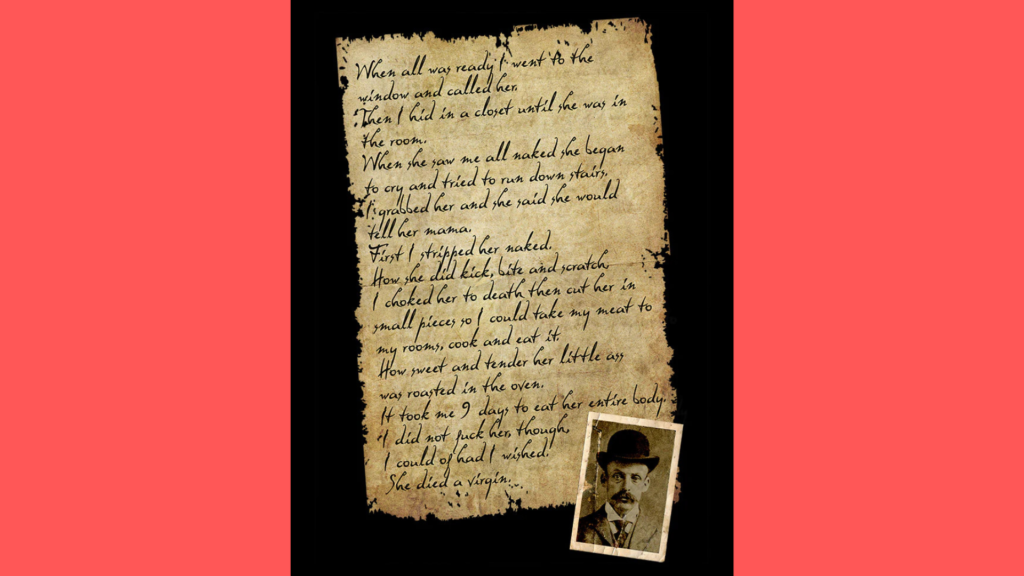

- The letter: Years after Grace’s disappearance, the Budd family received a letter whose contents were crucial not for what it said but what it was written on.

- Stationery clue: On the envelope was a small hexagonal seal associated with a chauffeurs’ benevolent association—a highly specific supply chain (not standard stationery) that investigators could trace.

- Follow‑the‑paper: Inquiry at the association led to the revelation that someone had taken a handful of that stationery and left it at a former rooming house. Detectives canvassed, waited, and prepared for a controlled encounter.

Arrest: the rooming‑house lead and a razor at the door

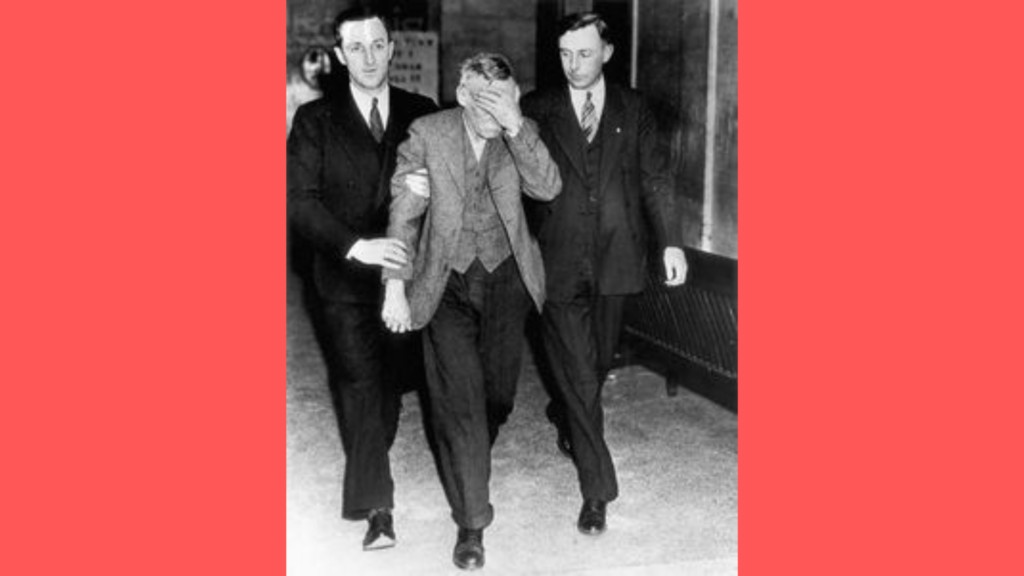

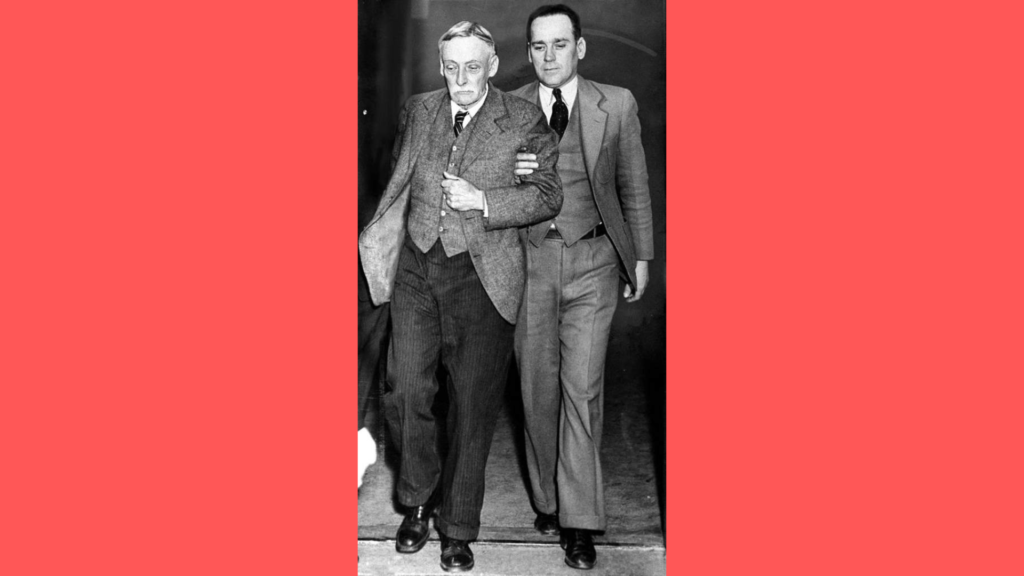

- Stakeout: Detectives surveilled the address linked to the stationery trail.

- Confrontation: When they approached Fish, he produced a razor in a sudden, defensive gesture. Officers quickly disarmed and arrested him, ending years of uncertainty.

- Post‑arrest: In custody, Fish gave statements that connected him to the Budd case and to other incidents investigators had been cross‑referencing.

Inside the White Plains trial (1935): Wertham vs. the State

- Venue & dates: White Plains, New York, in March 1935.

- Defense: Led by James Dempsey, centered on insanity claims. Psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham (later known for critiques of comic books) testified that Fish’s delusions—especially religious themes—meant he lacked criminal responsibility.

- Prosecution: Emphasized that Fish could plan crimes, evade capture, deceive victims and families, and modulate behavior—all signs he knew right from wrong.

- Jury question: Not “Is he abnormal?” but “Is he legally insane under M’Naghten?” The jury found him sane and guilty.

Execution at Sing Sing (1936): myths vs. facts

- X‑ray needles: Medical imaging showed numerous needles embedded in his pelvic region—evidence of longstanding self‑harm and masochism.

- Myth: “The needles short‑circuited the chair.”

- Fact: Contemporary accounts indicate the execution proceeded in typical fashion; the dramatic short‑circuit story is folklore, not documented reality.

- An elusive document: Fish’s lawyer later hinted at a written “final statement” he refused to make public, calling it profoundly obscene; no verified transcript has surfaced.

Psychological profile (non‑diagnostic): what experts debated

- Paraphilias & compulsions: Accounts discuss sadism/masochism, fetishistic rituals, and fixation on punishment.

- Religious coloring: Fish framed acts as divinely inspired, complicating the clinical picture.

- Capacity vs. responsibility: Even experts who considered him profoundly disordered differed on whether he met the legal threshold for insanity at the time of the acts.

Myth‑busting cheat sheet

| Claim | Reality |

| “Fish’s needles disrupted the electric chair.” | False. No reliable primary source validates a malfunction from needles. |

| “He confessed to a precise high victim count.” | Misleading. Numbers are uncertain; boasts and attributions vary. |

| “Wisteria Cottage has a single fixed address in all reports.” | No. Property numbering and references differ across sources; cite both when necessary. |

| “The Budd letter was solved by its content alone.” | Incomplete. The envelope and stationery chain were the key forensic leads. |

Why this case changed investigations

- Paper forensics: Logos, seals, watermarks, and supply chains can be as probative as fingerprints.

- Cover identities: The case illustrates the power of benign personas (elderly, kindly), now recognized in modern offender profiling.

- Inter‑agency handoffs: A niche organization (chauffeurs’ association) became the pivot—underscoring the value of non‑police institutional records.

Ethics of writing about true crime

- Non‑graphic detail. Focus on methods, prevention, and verified history.

- Dignity for victims. Use correct names, avoid sensationalism, and center the investigative milestones rather than lurid specifics.

- Transparency about uncertainty. Distinguish between documented facts, contemporary reports, and popular retellings.

Frequently Asked Questions (50 Q&As)

Q1. Why did the press settle on nicknames like “Gray Man” and “Werewolf of Wisteria” for Albert Fish?

These labels reflected both his frail, gray appearance and his association with Wisteria Cottage in Westchester County. The names helped newspapers frame the case for readers and have since shaped how searchers discover the story online.

Q2. Why was the Albert Fish trial held in White Plains instead of New York City?

Jurisdiction followed the crime scene: Wisteria Cottage sat in Westchester County, whose county seat is White Plains. That’s why the proceedings, including jury selection and verdict, took place there.

Q3. What made the Budd letter’s envelope such a decisive clue?

A small hexagonal association seal on the envelope linked the stationery to a specific organization. That niche supply chain was narrow enough for detectives to back‑trace the paper to a rooming‑house lead.

Q4. Did investigators rely on typewriter forensics for the Budd letter?

Typewriter analysis mattered far less than the paper trail. The envelope’s unique seal and sourcing provided the actionable lead that moved the case forward.

Q5. Why are there conflicting street numbers for Wisteria Cottage in various articles?

Historic renumbering, demolition, and later development have produced inconsistent address references in secondary sources. Responsible writers acknowledge the discrepancy rather than asserting a single “correct” number.

Q6. Was there a composite sketch of Albert Fish circulated at the time?

Not one that became definitive in the public record. Descriptions by witnesses and the eventual arrest photo filled the media space more than a widely recognized composite.

Q7. Did detectives consult postal clerks about the envelope beyond the seal?

Postmarks can narrow mailing windows, but in this case the decisive step was tracing the distinctive stationery itself. The supply‑chain inquiry outperformed generic postal timing.

Q8. How did rooming houses enable Albert Fish to avoid early capture?

Rooming houses allowed frequent moves, cash payments, and minimal background checks. That mobility made it harder for neighbors and landlords to connect him with past addresses.

Q9. Why did the defense lean so heavily on insanity rather than disputing facts?

Because many facts—his alias, movements, and incriminating letter—were difficult to refute. The defense strategy focused on legal responsibility under the M’Naghten rule instead of factual innocence.

Q10. What exactly is the M’Naghten rule and how did it apply here?

M’Naghten asks whether the accused understood the nature and wrongfulness of the act at the time. The jury concluded Albert Fish met that threshold and was therefore legally sane and guilty.

Q11. Did Albert Fish ever have a documented history of military service?

There’s no credible public record tying him to military service. His movements and work history were civilian and irregular.

Q12. Were early sex‑offender registries a factor in tracking him?

No. Modern registries did not exist in the 1920s–30s; investigators relied on witness work, paper trails, and inter‑agency calls.

Q13. Did police lift fingerprints from the Budd home that identified Fish?

Fingerprinting was known, but no single latent print from the Budd home is what broke the case. The stationery trail remained the pivotal lead.

Q14. Was there an undercover operation around Wisteria Cottage after the abduction?

Publicly available accounts emphasize canvassing, witness interviews, and later the letter‑trace stakeout in Manhattan, rather than a long‑term rural undercover operation.

Q15. Did Albert Fish keep detailed diaries that investigators recovered?

No such diaries are part of the standard public record. Much of what we know stems from interviews, letters, and trial testimony.

Q16. How did trolley and train lines expand his hunting ground?

Affordable rail and trolley routes connected boroughs and suburbs, letting a lone offender appear briefly, commit a crime, then vanish across jurisdictional lines.

Q17. Did the prosecution argue that planning proved sanity?

Yes. They highlighted deliberate acts—aliases, staged invitations, prepared locations—as evidence he understood right from wrong and could control behavior.

Q18. What role did newspaper classifieds play in the Budd case?

They were the original contact point: a small work‑seeking ad drew Albert Fish to the Budd family. Classifieds were a 1920s “marketplace” for labor and, unfortunately, for deception.

Q19. Are there authenticated photographs of Wisteria Cottage today?

A few historic images circulate, but the site changed over time. Researchers often rely on contemporary maps, property records, and local histories rather than recent photographs of the original structure.

Q20. Did the court ever consider commitment to an asylum instead of execution?

That outcome would have required a legal insanity finding. The jury rejected insanity and returned a guilty verdict, which carried a death sentence at the time.

Q21. Were jurors sequestered during the White Plains trial?

Media management varied by case and era. While the judge issued strict instructions, detailed records of full‑time sequestration aren’t widely available to the public.

Q22. Was there a formal sanity commission prior to trial?

Psychiatric examinations did occur, and experts later testified on both sides. Their disagreement framed the central legal question for the jury.

Q23. Did defense counsel request a bench trial instead of a jury trial?

No. The case proceeded to a jury, which weighed conflicting psychiatric testimony alongside circumstantial and documentary evidence.

Q24. Were there automatic appeals after the death sentence?

Capital cases typically triggered routine post‑trial review. No known appeal overturned the conviction or sentence.

Q25. Where are the pelvic X‑ray plates of Albert Fish today?

Public reproductions exist, but original materials are held in institutional or archival custody. Access is limited and typically requires permissions.

Q26. Did the needles in his body require any special adjustment to the electric chair?

No credible report shows that officials altered the procedure due to the needles. The oft‑repeated “short‑circuit” story is folklore.

Q27. Did Albert Fish show remorse in credible records?

His statements were often framed in religious terms rather than conventional remorse. Evaluators disagreed on how to interpret that posture.

Q28. Were any civil lawsuits filed by victims’ families related to the case?

Civil filings are not a prominent part of the public record for this matter. The historical focus remained criminal prosecution and execution.

Q29. Did the case directly change any state laws?

It did not produce a named statute. However, it entered training lore as a case study in material‑culture forensics (stationery, seals, supply chains).

Q30. Is there proof that Albert Fish used many aliases beyond “Frank Howard”?

“Frank Howard” is the best‑documented alias linked to the Budd approach. Additional names appear in anecdotes, but sourcing is thinner.

Q31. Was a handwriting expert used on any letters besides the Budd letter?

Public discussion centers far more on the letterhead and envelope than on handwriting analysis. The paper trail overshadowed stylistic examinations.

Q32. Did Fish ever attempt a plea to avoid a capital sentence?

There’s no reliable account of a successful plea arrangement. The defense focused on an insanity verdict rather than bargaining.

Q33. Were any of his family members called as defense witnesses?

Available reporting highlights psychiatric experts and law‑enforcement witnesses. Family testimony is not a major feature of most trial summaries.

Q34. Did the prosecution present physical evidence from Wisteria Cottage in court?

Evidence standards of the era prioritized testimonial linkage and documentary items. The case narrative leaned on movements, letters, and expert testimony rather than forensic science as we know it today.

Q35. Is there a surviving, authenticated transcript of the entire trial?

Newsroom transcriptions and court records exist in parts, but a complete, freely accessible transcript is not widely available online. Researchers consult archives for fuller coverage.

Q36. Did Dr. Fredric Wertham later publish a focused case study of Albert Fish?

Wertham wrote widely on crime and pathology, but no single monograph devoted exclusively to Fish dominates the literature. His views are best accessed through trial testimony and later essays.

Q37. How did newspapers shape public understanding of the case in the 1930s?

Headlines emphasized fear and nicknames, which helped the story spread but also solidified myths. Modern readers should cross‑check sensational claims against primary records.

Q38. Did the case influence parental safety advice in the U.S.?

It reinforced cautionary norms about children and strangers, especially promises of work, gifts, or parties. Community messaging increasingly stressed verification and supervision.

Q39. Was a formal victimology profile developed during the investigation?

Victimology as a discipline matured later. Still, detectives informally recognized patterns: age, vulnerability, and the offender’s grandfatherly persona.

Q40. Did investigators examine stationers or printers for similar hexagonal seals?

Yes—supply‑chain questioning is implied by the successful trace to a specific association. That narrow provenance is why the envelope mattered so much.

Q41. Were any maps or transit schedules used in court to explain Fish’s movements?

Contemporary press suggests movements were discussed narratively. Visual exhibits were not the centerpiece; the letter‑trace story was.

Q42. Did the judge give any notable instructions that shaped the verdict?

The key instruction concerned the legal definition of insanity. Jurors were reminded that moral revulsion is not the standard—knowledge of wrongfulness is.

Q43. Was there any credible evidence that Albert Fish had accomplices?

No. Accounts consistently depict him as a solitary offender relying on deception and mobility.

Q44. How did the public react immediately after the execution?

Coverage peaked around the verdict and execution, then tapered into retrospectives. The case persisted as a cautionary tale rather than an ongoing controversy.

Q45. Are there memorials or plaques for victims tied to the case?

Nothing widely publicized exists at a national level. Remembrance tends to be private or local rather than formal monuments.

Q46. What practical lesson do modern investigators cite from this case?

Small material details—watermarks, seals, paper sources—can be more decisive than dramatic confessions. Following supply chains can localize a suspect quickly.

Q47. How can researchers verify claims in online articles about Albert Fish?

Start with contemporaneous newspapers, county court records, and reputable archives. Treat unsourced quotes and sensational details with skepticism.

Q48. Are there known prison medical notes about managing the needles in his body?

Medical observations exist in summary form in historical reporting, but detailed clinical files are not broadly available to the public.

Q49. Did the execution drawing many press witnesses compared to typical cases?

Witness lists were controlled. Reports suggest a standard complement of officials and limited press rather than a spectacle in the chamber.

Q50. What modern analogue best captures the stationery clue’s importance?

Think of it like digital metadata or device‑specific watermarks today: a subtle identifier that can shrink a suspect pool and anchor a search to a physical place.