Introduction

The Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE), conducted in 1971 by psychologist Philip Zimbardo at Stanford University, remains one of the most infamous psychological studies ever conducted. It aimed to explore the psychological effects of perceived power, focusing on the struggle between prisoners and prison guards. What started as a two-week experiment had to be terminated in just six days due to the extreme psychological distress experienced by participants.

This blog delves deep into the experiment, its findings, ethical concerns, and its long-lasting impact on psychology and social behavior.

The Background of the Experiment

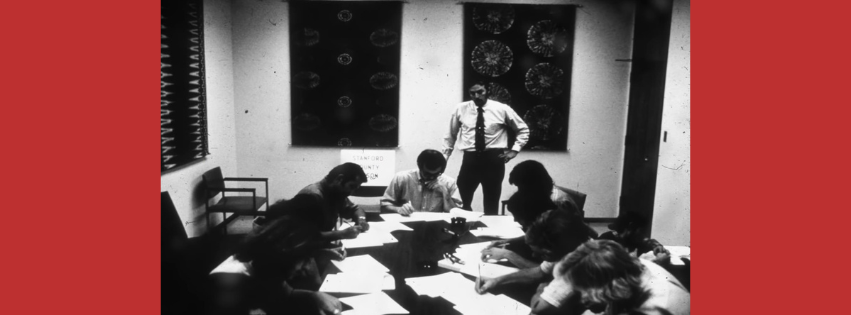

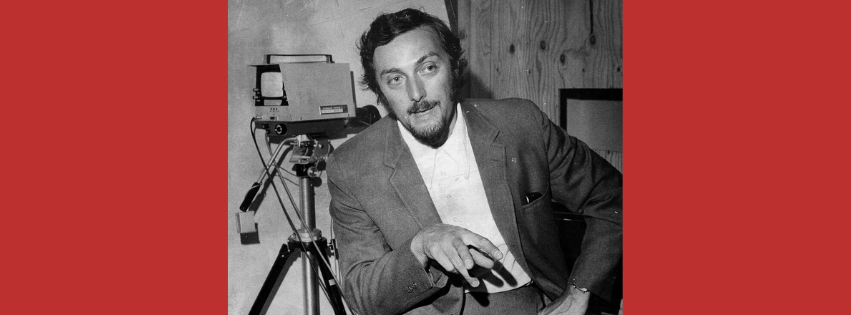

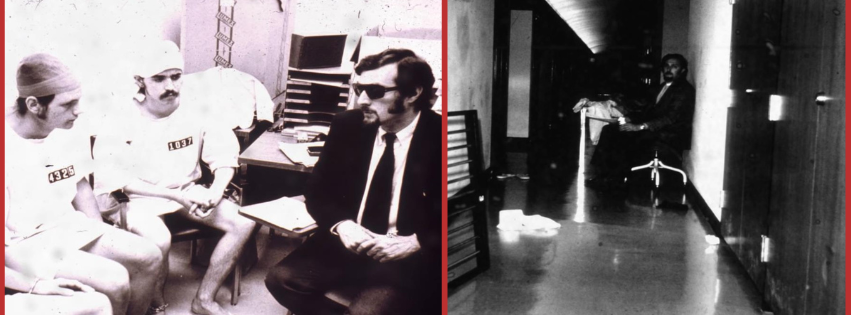

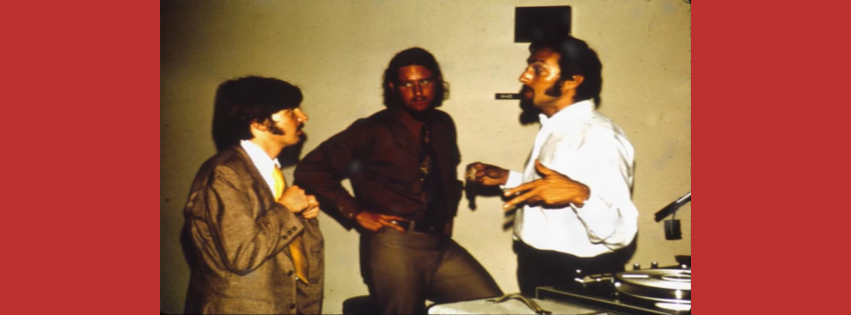

Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues wanted to investigate whether people behave abusively due to inherent personality traits or if situational factors influence their actions. They created a mock prison in the basement of Stanford University and recruited 24 male college students who were randomly assigned roles of either guards or prisoners.

The Setup

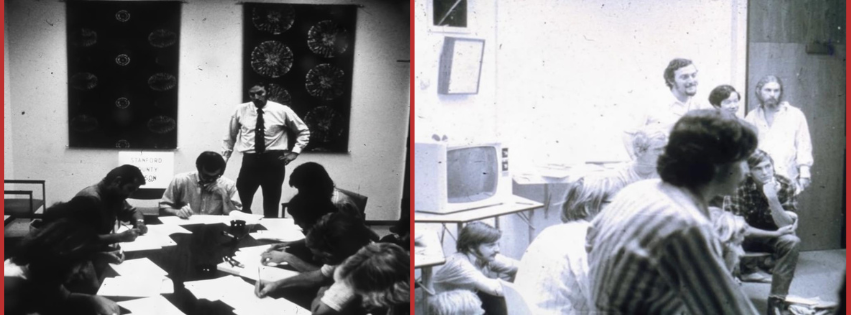

- Selection of Participants: 24 healthy male students were chosen after rigorous psychological screening.

- Random Assignment: Participants were randomly assigned the role of either prisoner or guard.

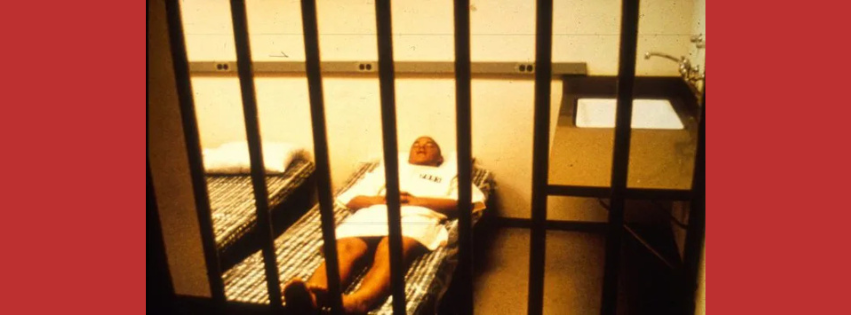

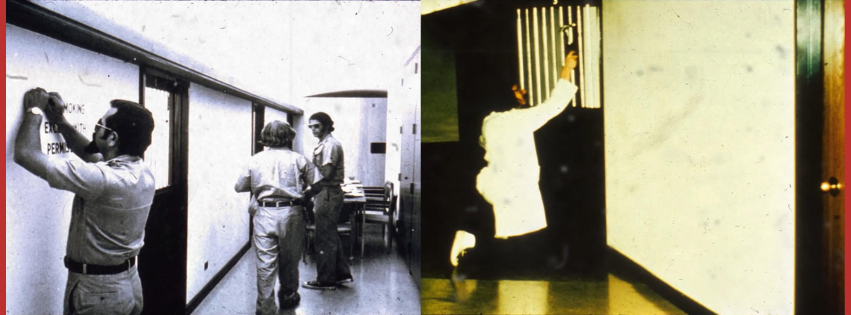

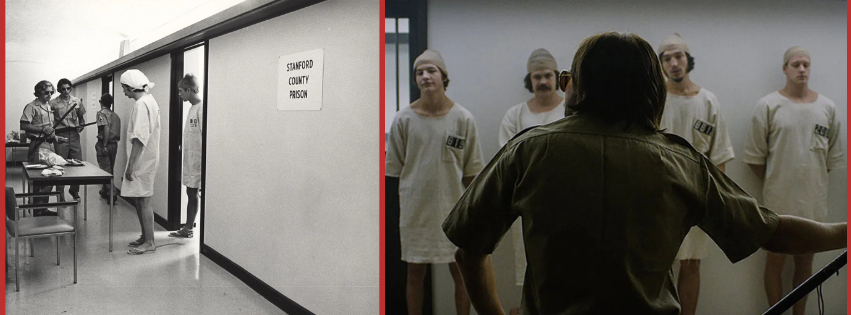

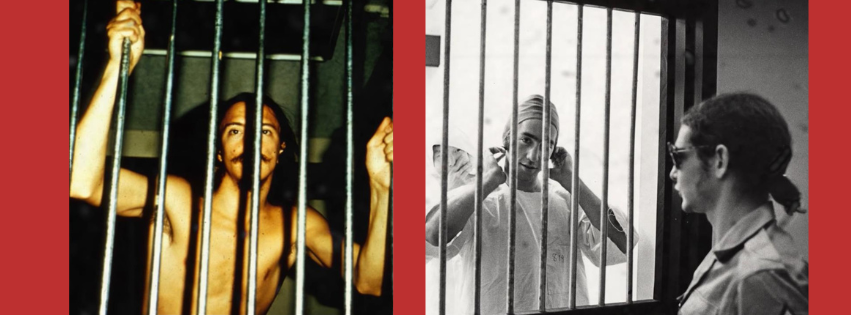

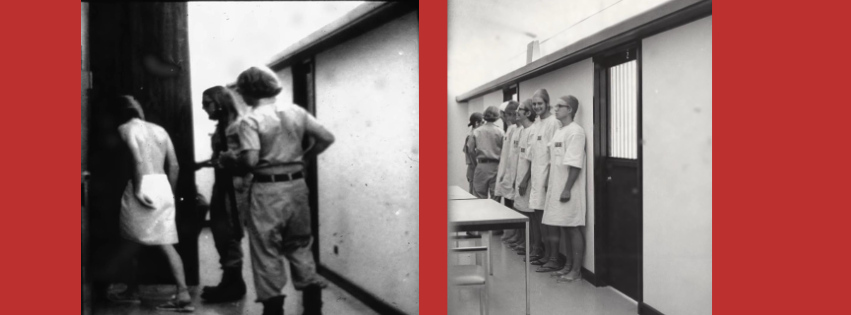

- Mock Prison: A makeshift prison was built in the basement of Stanford University, complete with barred doors, narrow hallways, and small cells.

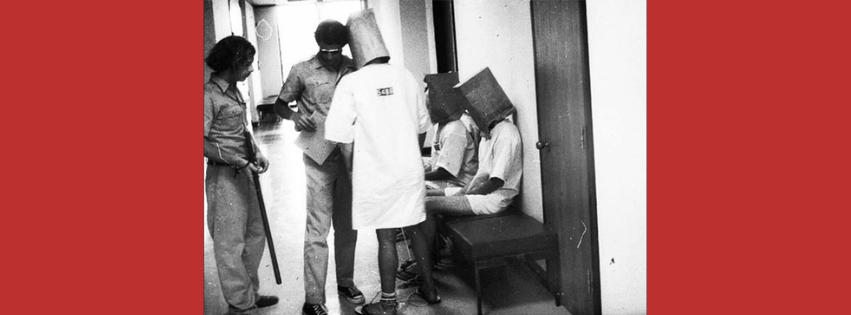

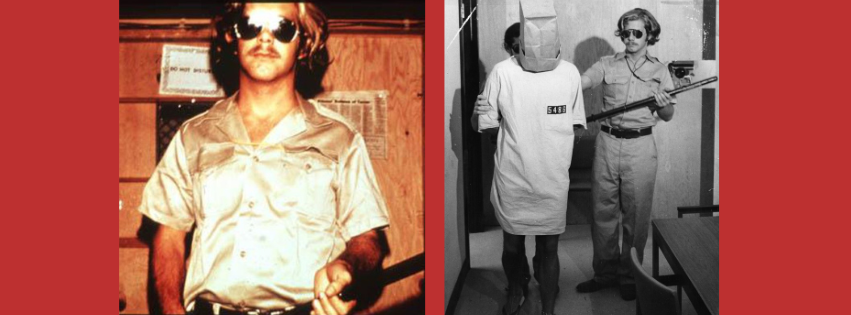

- Uniforms and Rules: Guards were given batons, mirrored sunglasses, and military-style uniforms. Prisoners were given numbered smocks, had their identities stripped, and were referred to only by their assigned numbers.

- Supervision: Zimbardo himself took on the role of prison superintendent, while other researchers played supporting roles in maintaining the prison environment.

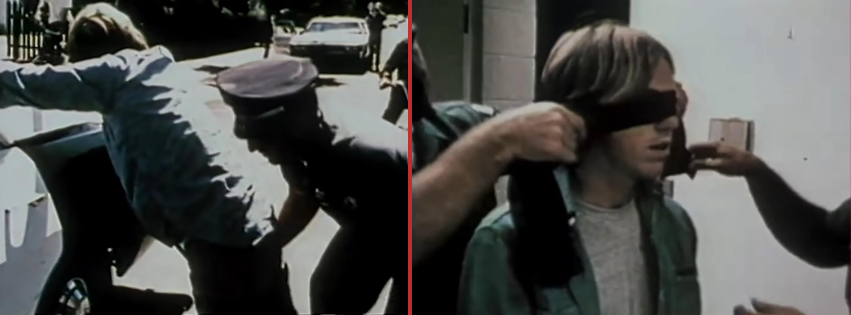

- Psychological Preparation: Prisoners were “arrested” at their homes by real police officers, adding an element of realism to the study.

The Unfolding of the Experiment

Day 1: Establishing Roles

Initially, the participants hesitated in their roles. The guards were unsure how strict they should be, and the prisoners did not resist their treatment. However, as the day progressed, the guards became more assertive in their authority, and the prisoners started feeling the effects of their powerless positions.

Day 2: The Rebellion

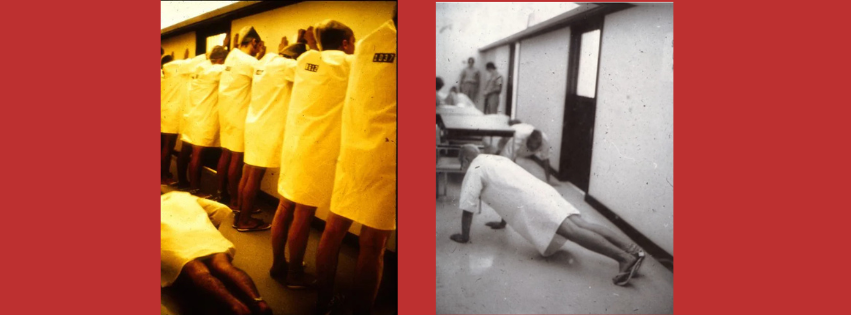

By the second day, some prisoners began rebelling against the guards, refusing to follow orders and barricading themselves inside their cells. The guards responded with psychological tactics, such as using fire extinguishers to force prisoners out and imposing harsh punishments, like sleep deprivation and solitary confinement.

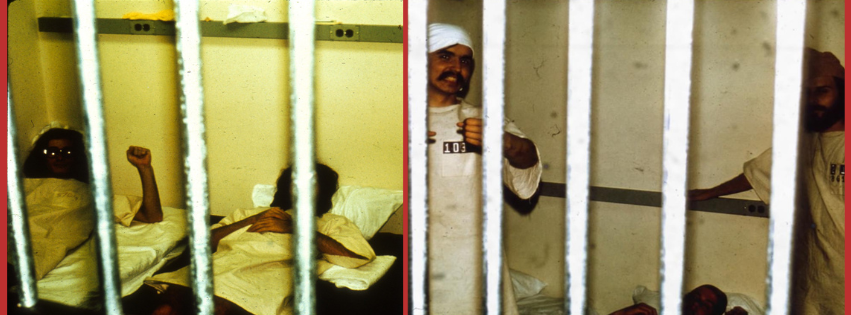

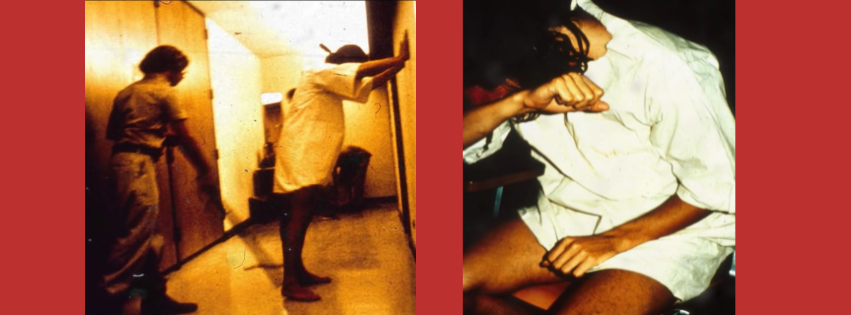

Day 3-4: Escalation of Abuse

The guards became increasingly cruel, forcing prisoners to engage in degrading tasks such as cleaning toilets with their bare hands, stripping naked, and performing humiliating acts. Some guards derived enjoyment from exerting power over the prisoners, while others followed along to maintain order. Psychological abuse intensified, and prisoners showed signs of extreme stress, anxiety, and emotional breakdowns.

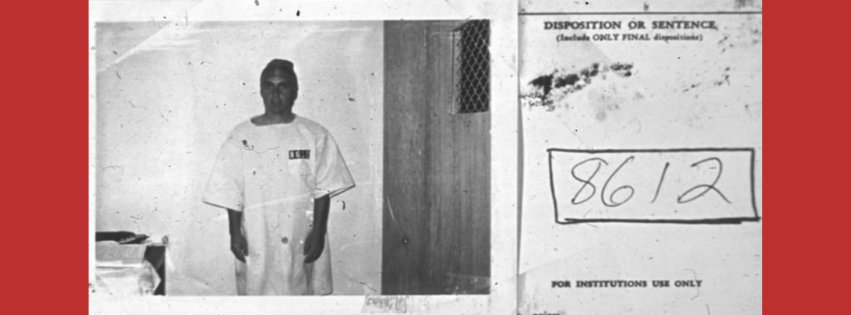

Day 5: Emotional Breakdown and Intervention

One prisoner, identified as #8612, suffered an emotional breakdown and had to be released. Other prisoners displayed signs of trauma, begging to be let out. Despite these warning signs, Zimbardo allowed the experiment to continue until his colleague, Christina Maslach, visited the prison and expressed shock at the conditions, urging him to end the study.

Day 6: The Termination

After realizing the extent of the psychological harm inflicted on participants, Zimbardo called off the experiment. Though initially planned for two weeks, it lasted only six days due to the ethical and moral concerns raised.

Ethical Concerns and Impact

Major Ethical Issues

- Lack of Informed Consent: Participants were not fully aware of the potential psychological harm they would endure.

- Right to Withdraw: When some prisoners wanted to leave, they were persuaded to stay, violating ethical research principles.

- Psychological Harm: Participants experienced severe emotional distress, trauma, and humiliation.

- Zimbardo’s Role: As both the lead researcher and the “prison superintendent,” Zimbardo failed to maintain objectivity and allowed unethical behavior to continue.

Impact on Psychological Research

The Stanford Prison Experiment became a catalyst for major reforms in psychological research ethics. The American Psychological Association (APA) and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) now enforce strict guidelines to protect participants in studies involving human subjects. Researchers must ensure voluntary participation, informed consent, and the right to withdraw at any time.

Influence on Real-World Institutions

- Prison System Reforms: The study highlighted the dangers of unchecked power in prisons, influencing discussions on prison reform and rehabilitation programs.

- Military and Law Enforcement: It provided insight into the psychological effects of power, explaining behaviors observed in cases such as the Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal.

- Workplace and Social Hierarchies: The findings extend beyond prison environments, showing how authority figures can misuse power in various institutions.

50 Unique Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About The Stanford Prison Experiment

General Questions

- Why was the Stanford Prison Experiment originally planned for two weeks?

It was designed to allow enough time for participants to adjust and show behavioral patterns in a controlled environment. - What role did Philip Zimbardo play in the experiment?

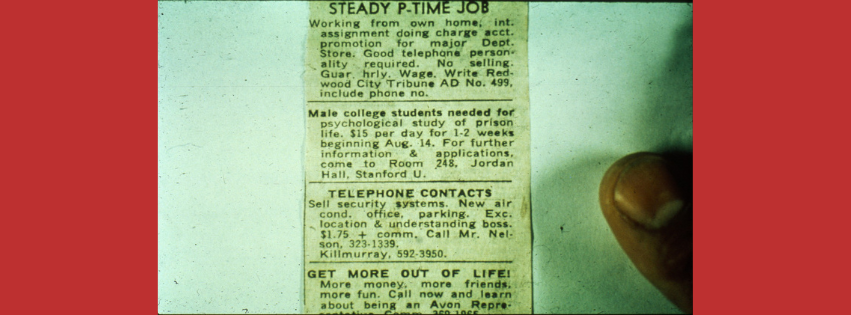

He acted as the prison superintendent, overseeing the interactions but failed to maintain an objective role. - How much were participants paid?

They were paid $15 per day, which was a reasonable compensation for the time. - What led to the premature end of the experiment?

Extreme psychological distress, emotional breakdowns, and ethical concerns led to its termination after six days. - How did Zimbardo recruit participants?

Through a newspaper advertisement calling for volunteers for a psychological study on prison life.

Psychological and Ethical Implications

- Did any participants suffer long-term psychological effects?

Some reported lingering distress, but no documented permanent psychological damage was found. - What ethical guidelines were violated?

Informed consent, right to withdraw, and protection from harm were compromised. - What changes did this experiment bring to psychological research ethics?

It led to stricter ethical guidelines, requiring IRB approval for all human research studies. - Could such an experiment be conducted today?

No, due to stringent ethical regulations preventing such high-risk studies. - How does this experiment relate to real-world prison environments?

It demonstrated how power dynamics and institutional settings contribute to abusive behavior.

- Were the guards given specific instructions on how to behave?

No, the guards were not given specific guidelines on how to enforce discipline. They were free to create their own rules, which led to extreme behavior. - Did any guards refuse to participate in the abusive behavior?

Some guards were less aggressive, but none actively intervened to stop the abuse. - Were there any female participants in the experiment?

No, all participants were male college students. However, Zimbardo’s then-girlfriend Christina Maslach played a crucial role in stopping the experiment. - Did Zimbardo conduct follow-up studies on the participants?

Yes, follow-ups were conducted months and years later, with some participants reflecting on how the experience affected them. - Did the experiment have any connection to the Milgram Experiment?

Yes, both studies examined obedience and authority, showing how people conform to roles under pressure. - What legal actions, if any, were taken against Zimbardo or Stanford University?

No legal actions were taken, but the experiment contributed to stricter ethical guidelines in psychological research. - Did the prisoners and guards ever reconcile after the experiment?

Some participants later met and discussed their experiences, but not all maintained contact. - Was the experiment replicated in other countries?

Similar studies have been conducted, including BBC’s “The Experiment” in 2002, which had different results. - Were there any physical injuries during the experiment?

No severe physical injuries were reported, but there was extreme psychological distress. - What was the public reaction when the results were published?

The experiment was both praised and criticized, sparking debates on ethics and human behavior. - Did any of the participants experience PTSD after the experiment?

While no official PTSD diagnoses were recorded, some participants reported lingering emotional distress for years. - How did the experiment impact Zimbardo’s career?

The study made him famous but also sparked criticism about his ethical judgment. - Did the guards express remorse after the experiment?

Some guards later admitted feeling guilty about their actions, while others justified their behavior. - Were there any external influences on the participants’ behavior?

The simulated environment, peer pressure, and Zimbardo’s role as superintendent contributed to the behavior changes. - What role did Christina Maslach play in ending the experiment?

She was the first to strongly criticize the experiment’s ethics, which led Zimbardo to terminate it early. - Did any organizations use the findings of the Stanford Prison Experiment?

Military and correctional institutions studied the findings to understand power abuse and behavior under authority. - What other experiments have been influenced by the Stanford Prison Experiment?

The BBC Prison Study (2002) was a notable replication with different results, highlighting individual agency over roles. - Did Zimbardo face any professional consequences for the experiment?

Though criticized, he remained a respected psychologist and professor, later advocating for ethical reforms. - Why did the guards escalate their abusive behavior?

Lack of accountability, group mentality, and situational power dynamics fueled their increasingly aggressive actions. - Did prisoners ever try to resist their assigned roles?

Yes, but resistance was met with escalating punishments, reinforcing their learned helplessness. - Were any strategies in place to protect participants from harm?

No effective safeguards existed, which is why the experiment is widely criticized today. - How did the participants react immediately after the experiment ended?

Many were relieved, some were shocked by their actions, and a few needed counseling to process the experience. - What role did the media play in shaping public perception of the experiment?

Extensive media coverage amplified both praise and criticism, shaping its controversial legacy. - What specific conditions in the mock prison led to extreme behavior?

Isolation, lack of oversight, dehumanization, and arbitrary punishments intensified the psychological effects. - How does the experiment compare to real-world prisoner experiences?

Though exaggerated, it mirrors real instances of prison abuse, such as in Abu Ghraib and other institutions. - Did the experiment have an official peer review process?

While published, it lacked rigorous peer review, raising concerns about its scientific credibility. - What lessons can workplaces learn from the experiment?

It highlights how unchecked authority and hierarchical structures can lead to abuse and unethical behavior. - Did Zimbardo ever apologize for the experiment?

He defended his study but later admitted its ethical shortcomings and used it as a lesson for research ethics. - Was the experiment’s design flawed?

Yes, due to role-playing biases, lack of oversight, and Zimbardo’s dual role as both researcher and superintendent. - What modern psychological concepts relate to the experiment?

Concepts like deindividuation, learned helplessness, and social identity theory relate to its findings. - How does the experiment relate to social media and online behavior today?

It demonstrates how anonymity and authority structures influence group behavior, including online bullying. - Did the guards face any consequences after the experiment?

No formal actions were taken against them, but some personally struggled with their actions. - What were the biggest criticisms of the study?

Ethical violations, lack of scientific rigor, and Zimbardo’s involvement as a participant compromised objectivity. - How does the study influence law enforcement training?

It serves as an example of power misuse, leading to discussions on police accountability and ethics. - What alternative explanations exist for the participants’ behavior?

Some argue demand characteristics and expectations played a larger role than true psychological transformation. - Has the experiment’s validity been challenged?

Yes, critics argue it lacked proper controls and was more of a dramatization than an objective study. - Did any cultural factors play a role in the experiment?

The study took place in the U.S., where authority structures and media portrayals of prisons influenced participants. - How do modern psychologists view the Stanford Prison Experiment?

Opinions are divided—some see it as groundbreaking, while others dismiss it as flawed and unethical. - What impact did the study have on academic psychology?

It contributed to discussions on ethics, power dynamics, and the replication crisis in psychology. - Would results differ if the study was conducted today?

Likely, due to ethical oversight and increased awareness of the experiment’s controversial nature. The Stanford Prison Experiment remains a controversial yet insightful study into human psychology, power dynamics, and ethical boundaries in research. While it shed light on the dangers of unchecked authority, it also served as a cautionary tale for future research. Its legacy continues to influence psychological studies and discussions on ethical considerations in research and real-life institutions.

Conclusion

The Stanford Prison Experiment remains a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked power, the fragility of ethics in research, and the extent to which situational forces shape human behavior. While its findings are debated, its influence on psychology, ethics, and criminal justice endures.